Lesson 3: Rules of Perspective

What is linear perspective, and how is it different from aerial perspective? What are vanishing points and horizon lines? Let’s find out.

Perspective is a fundamental concept in drawing that helps artists represent objects in space as they appear to the human eye. Understanding perspective allows you to place forms correctly on the page, making your drawings look realistic and spatially accurate.

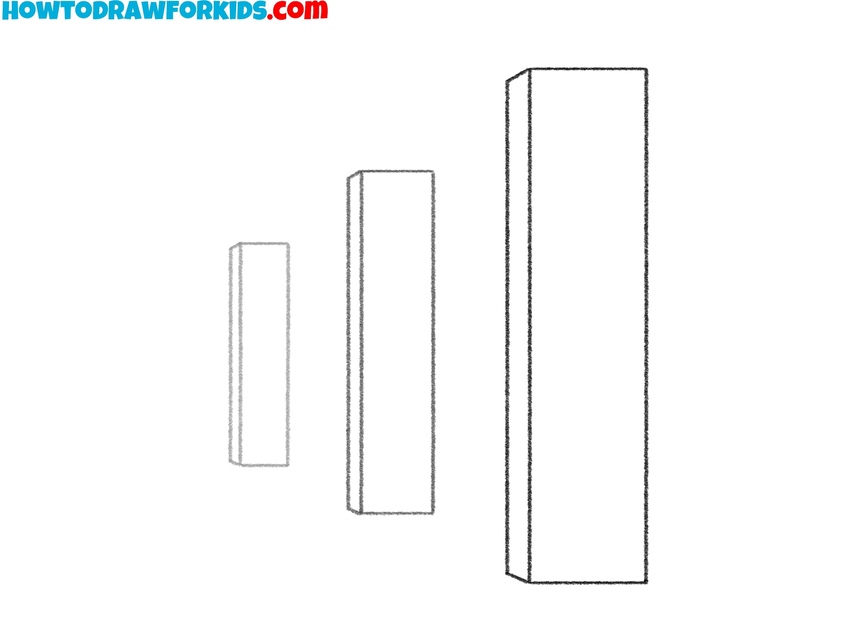

When we observe the world around us, objects change in appearance depending on their distance from the viewer. A nearby building appears larger and more detailed than the same building seen far away. The lines of streets, railway tracks, and rows of trees seem to converge as they recede into the distance. These distortions follow specific rules of perspective, which were studied and formalized over centuries of artistic practice.

Linear Perspective

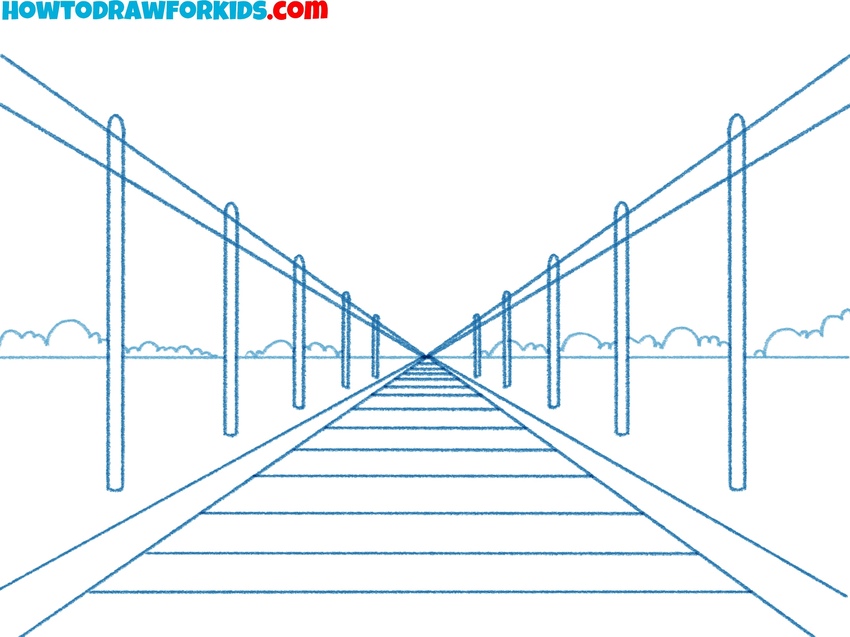

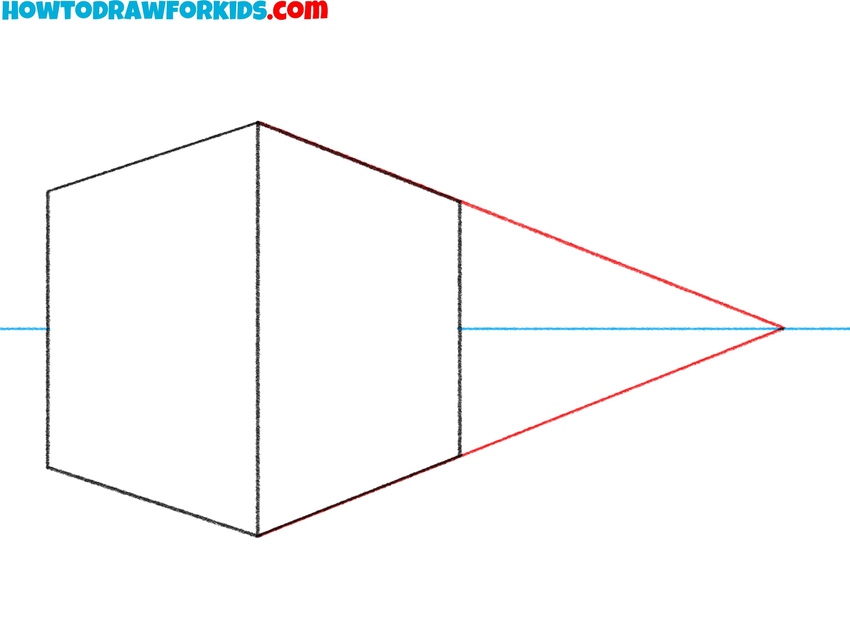

Linear perspective deals with the visual shortening of objects as they recede in space. This effect is based on the position of the observer’s eye, also called the “viewpoint” or “point of view”, and the way objects align relative to it. The farther an object is from the viewer, the smaller it appears. At the heart of linear perspective is the principle that parallel lines appear to converge toward one or more vanishing points on the horizon line.

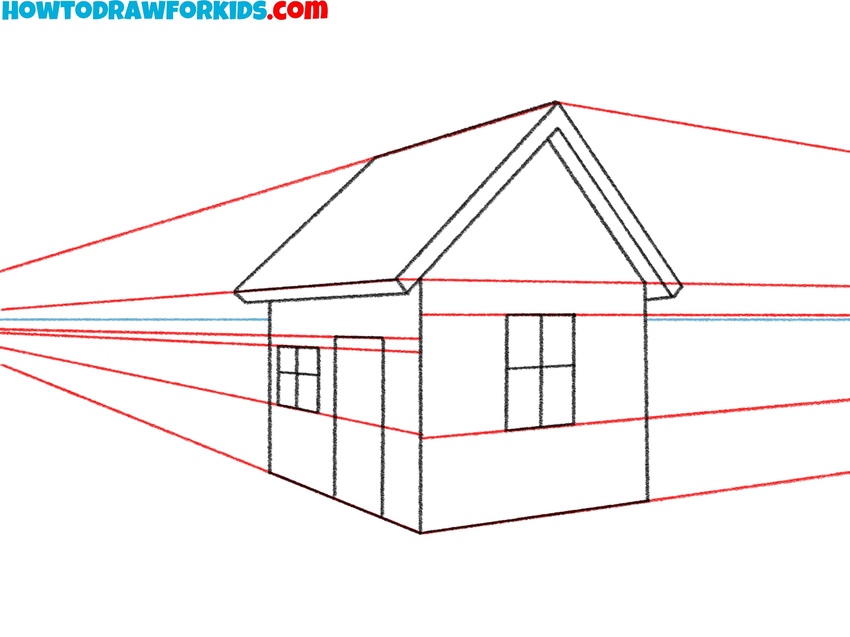

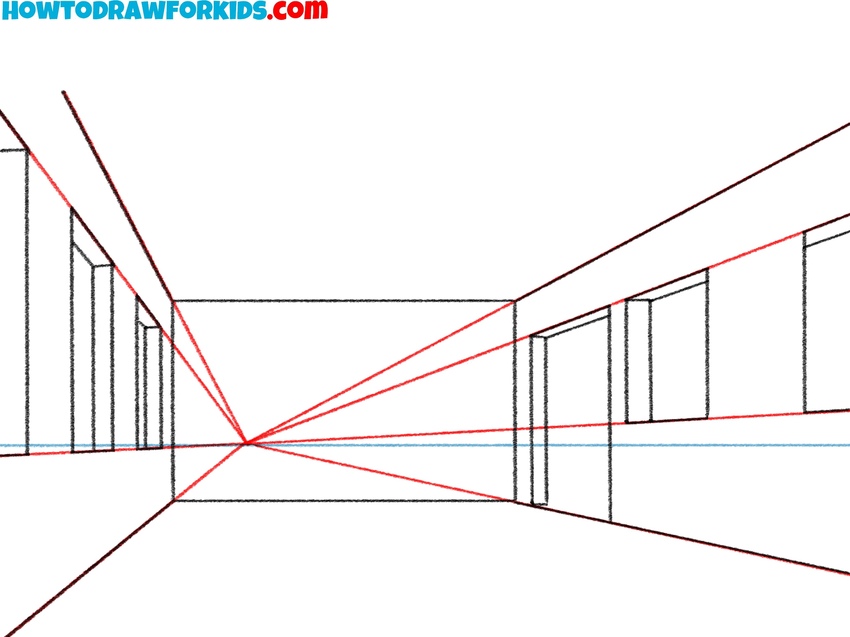

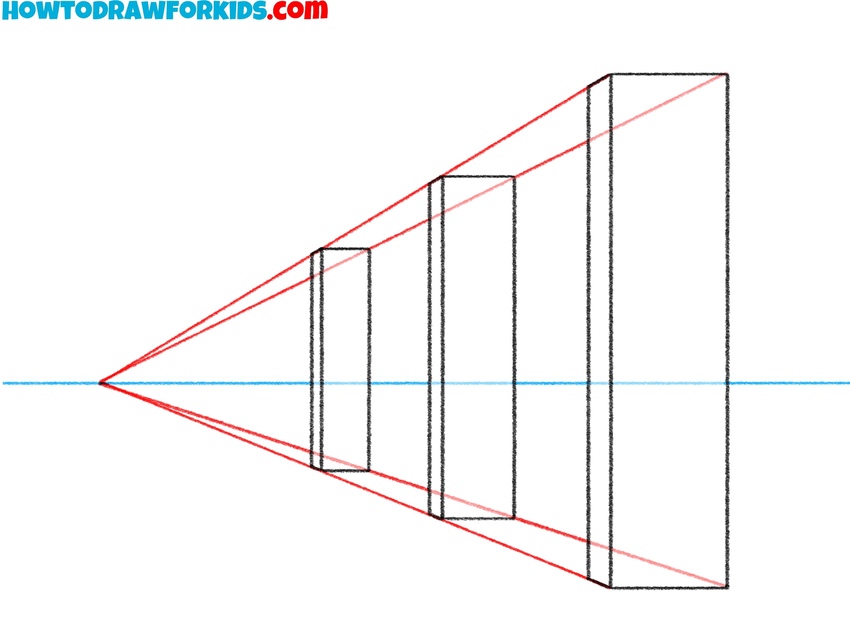

Linear perspective teaches how to project three-dimensional objects onto a flat surface, using vanishing points and a horizon line. One-point, two-point, and three-point perspective systems help artists construct scenes where all lines converge toward specific points on the horizon.

The horizon line represents the viewer’s eye level. If you look straight ahead, it corresponds to a horizontal plane cutting through your field of vision. Every object in the scene is placed in relation to this line. Parallel lines that are not perpendicular to your line of sight appear to angle toward vanishing points that lie on the horizon.

In one-point perspective, all receding lines converge at a single point directly in front of the viewer. This type of construction is often used when drawing roads, railway tracks, or hallways seen head-on. Two-point perspective is used when the object is rotated, such as a cube seen from the corner. Each set of horizontal lines converges toward its own vanishing point on the horizon, creating a more complex illusion of realism.

Vertical lines usually remain parallel in these systems, unless the viewer looks up or down. In those cases, vertical perspective comes into play, and additional vanishing points above or below the horizon may be needed to describe foreshortening properly.

The picture plane is the imaginary transparent surface between the viewer and the subject. It’s as if the scene is projected onto a vertical pane of glass. The ground plane refers to the horizontal surface objects rest on. Together, they help organize the spatial placement of forms.

So, the key rule of linear perspective is this: objects appear smaller the farther they are from the viewer, and parallel lines seem to converge as they recede.

Failing to apply perspective leads to common mistakes: skewed angles, incorrect scaling, and flattened forms. That’s why it’s important to understand where the horizon is, how vanishing points affect object placement, and how to use these elements to organize space.

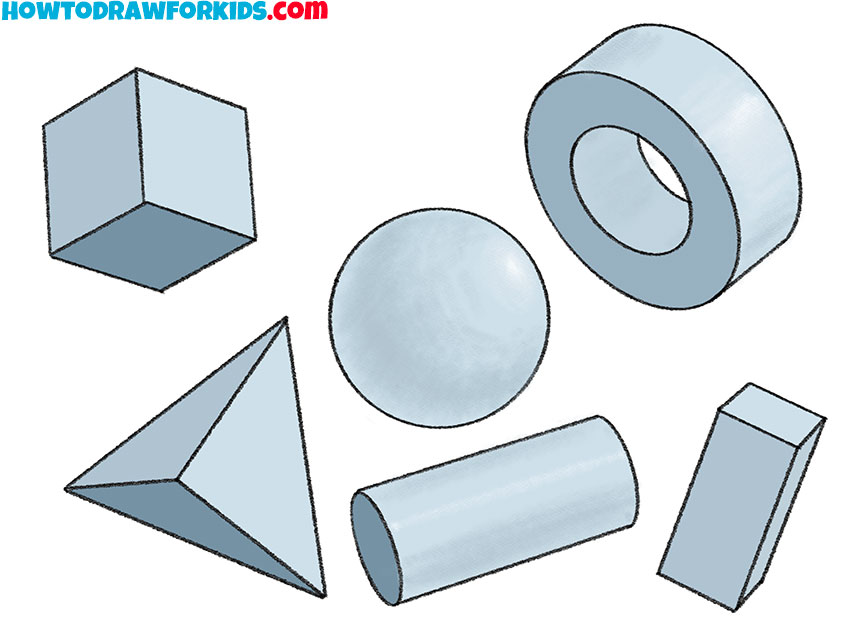

Perspective also influences how curved forms are perceived. A circle on a horizontal surface, when viewed at an angle, appears as an ellipse. This change must be accounted for in drawings of cylinders, spheres, and other round objects. Incorrect ellipses break the illusion of form and realism.

Aerial Perspective

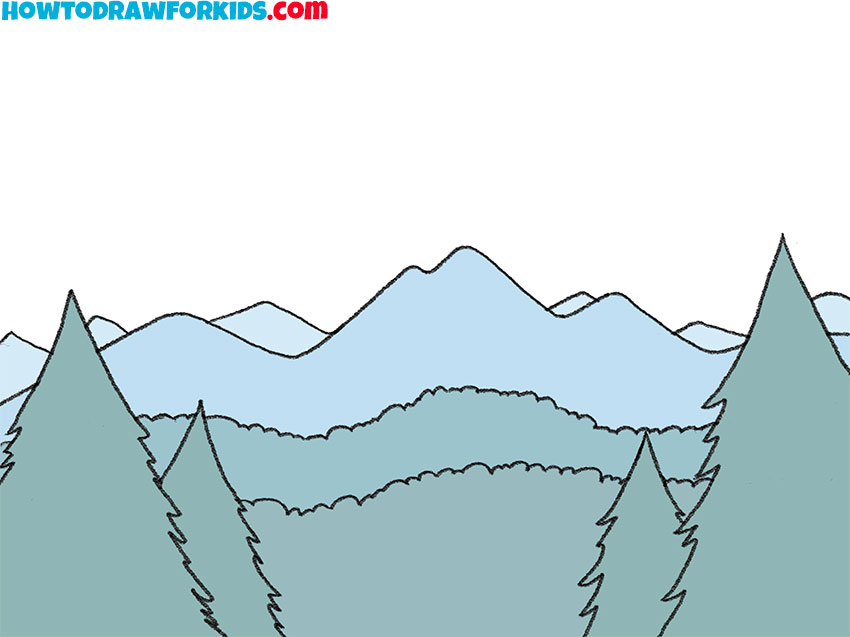

In addition to linear methods, artists use aerial or atmospheric perspective to convey the realistic view. This is based on the way the air affects our perception of distant objects. The farther away something is, the more it is affected by the atmosphere between it and the viewer.

As objects recede, they tend to appear lighter, bluer, and less distinct. Edges become softer, contrast decreases, and fine details disappear. This is not just a stylistic device, it reflects the actual optical behavior of light scattering in the air.

A classic example is a mountain range. The closest mountains are sharply defined and richly colored. Those farther away become cooler in tone, lighter in value, and softer in outline.

Artists use atmospheric effects deliberately, even in indoor settings. A foreground object may be drawn with strong contrast and sharp detail, while the background is handled with minimal lines and lighter shading. This creates the illusion of space without changing the underlying perspective construction.

Practice

To develop a strong sense of perspective, start by observing how objects change with distance. Notice how lines converge, how shapes tilt, and how sizes shift depending on your point of view.

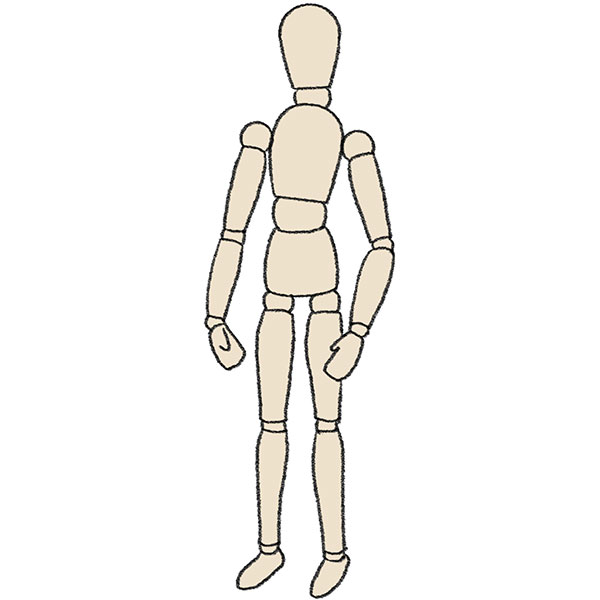

Begin practicing with simple forms, draw cubes, boxes, and cylinders. Place them above, below, or directly on the horizon line to see how their appearance changes. Draw them from observation and memory. Identify the horizon line and vanishing points in each case.

Practicing these exercises regularly will train your eye to see structure and direction, helping you build solid, believable forms in any drawing.

Conclusion

Understanding both linear and aerial perspective gives you the tools to place objects accurately in space, control the viewer’s attention, and create believable three-dimensional drawings. Learning how forms change with distance, how lines behave in space, and how atmosphere affects appearance will make your drawings more realistic.